30 Ago Afghanistan: Human Rights, Women and Freedom of Speech: Solid Fears

Afghanistan

Human Rights, Women and Freedom of Speech:

Solid Fears

“I am not optimistic. I cannot be optimistic. The situation of women will be worse day by day… Because of our history and what we have been through, women and children are very scared.” -Humira Saqib, 41, Afghan journalist, co-founder of the Afghan Women news agency.

WOMEN AND THE RETURN OF THE TALIBAN REGIME

A little more than two decades ago, between 1996 and 2001, women were marginalized during the Taliban’s control of Afghanistan. Today, in regions under Taliban rule, measures that violate women’s human rights have been imposed. Some of these repressive measures focus on forbidding work outside the home, education, and access to public life in general. A number of human rights organizations have condemned these abuses, such as Women for Afghan Women, which works to support disenfranchised Afghan women and children in Afghanistan and New York by providing essential services, protection and education.

“In Afghanistan there were more than three hundred women active in the media, more than three thousand in government or bureaucratic positions and also a good number of women entrepreneurs. All that is over. The Sharia, which is the fundamentalist belief that the Taliban are going to impose, means that a woman cannot even go out on the street without a man accompanying her.”

This is one of Humira Saqib’s answers, in a virtual interview conducted by Rodrigo Sosa.

Since August 14, the whole world has been holding its breath awaiting the departure of the US troops and their allies from this Central Asian country and the entry of the Taliban into the capital, Kabul. Despite the obvious signs of what was already happening in various parts of the territory and despite the many years of occupation, the initial flights withdrawing troops and officials became an ominous sign of the immediate future for Afghan citizens, especially women and children.

Sharia or Islamic Law is a code of moral conduct based on a radical and extremist interpretation of the Koran and other Islamic scriptures; not being a religious dogma, however, it is used as a practice only by a limited number of Muslims and as law in some places that call themselves Islamic States. The Sharia imposed by the Taliban excludes women from public life, work and education, punishing them severely if they go out without a male escort, have expressive or affectionate displays on the street or show any part of their bodies.

Saqib’s central concern, like that of much of the world, revolves around the consequences that the return of Taliban rule to Afghanistan may bring back:

“I lived through that regime, I lived through those years and that is why I am leaving the country. In my opinion all women who can should leave because with the Taliban, women will not have the freedom to go out onto the street, or to dress as they want, or to choose a husband, or to study or work. They will not even have the right to show their ankles or open their windows. They will be left without education, without work, without being able to choose their husband, without being able to choose their future and without even being able to leave their homes or appear in the public space. Do you think that is life?”

DECADES OF CHANGE: AFGHANISTAN’S WOMEN IN DATA

By searching open data sources on Afghanistan, we explore variables that can, in the aggregate, illustrate the changes in living conditions and development that the female population in that country has experienced in recent decades. It also allows us to capture the current panorama of Afghan women’s lives, which could be at risk from the threat of the establishment of a regime that would force them to take steps backward from the progress they have achieved.

According to the records and estimates published by the World Bank’s open data portal on Afghanistan, we can highlight the following observations among the indicators analyzed:

Population

- Population, female (% of total population). In the last 20 years there was a pronounced growth in the population, including the proportion of women. As of 2020, 48.69% of the Afghan population is female.

- Of the female population in 2020, 41.93% are under 14 years old, 11.88% are between 15 and 19 years old, and 10.07% are between 20 and 24 years old. In other words, more than 60% of women are young people in the stage of social, physical and educational development.

FIG. 1 Afghanistan: Female population by age groups 1960-2020. Source: World Bank. Population of women in Afghanistan, total and percentages by age group.

Education

- Literacy rate, young women (% of women aged 15-24). Although continuous data are not available, between the last two years recorded (2011 and 2018) there was an increase of over 20%, from 32.11% to 56.26%, showing a greater increase than in the Middle East during that same period (2%), although remaining more than 30% below the percentage of that region.

- Literacy rate, adult women (% of women aged 15 and over). Lowest numbers recorded in the region -below Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh-, however, they present an increase of more than 10% from 2011 to 2018, from 17.01% to 29.80%. At the same time, the rate is lower by more than half than that of the Middle East, which in 2018 was 72.35%.

- School Enrollment Rate, primary level, female (gross %). Peaked in 2014 at 87.73%, remaining above 82% since then, contrasting with 3.84% in 1999.

- Persistence up to the last grade of primary school, female (% of cohort). No data after 1977, when the rate was 77.65%.

- Progression to secondary school, female (%). The latest 2017 data indicate that 85.55% of females graduating from primary school continue on to secondary school. Previous data do not drop below 80% after 2015, although prior to that date, there is no information after 1984.

FIG. 2: Afghanistan: School enrollment, primary level, males and females 1970-2020. Source: World Bank. Gross Enrollment Rate. “May be higher than 100% due to the inclusion of students older and younger than the official age because they either repeated grades or by early or late entry to entered that level of education early or late.”

Health

- Suicide death rate, female (per 100,000 female population). Starting from the first year data are available, 2000, the rate dropped from 4.8 to 3.4 in 2017. Since then, the rate has increased 2 tenths to 4.6. Men see an increase in the suicide death rate after 2014, and it has held steady since 2017 at 4.6.

- Women making their own informed decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use, and reproductive health care (% of women aged 15-49). No data available.

- Teenage mothers (% of women aged 15-19 who have had children or are currently pregnant). The only record is from 2015 and it indicates 12.1%, no data available for comparison with the Middle East or surrounding countries.

Economy

- Labor force, women (% of total labor force). Since 2008 there has been a steady increase from 15.40 of the labor force to 21.60 in 2019. Thus, in its region, it only surpasses India, the Maldives and Pakistan in terms of percentages. It exceeded, in 2018, the average of the Arab World and the Middle East, by 1%.

- Share of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, women (% of 24 hours per day). No data available.

FIG. 3 Afghanistan and neighboring regions: Percentage of women in the economically active population

Source: World Bank. Labor force, women (% of total labor force) – Afghanistan, Arab World, Middle East and North Africa.

As can be seen from the available data, all indications are that the lives of Afghan women, in general, have been steadily improving. The arrival of a regime that subordinates and excludes women may imply significant setbacks that will even have repercussions at the regional level. Some key questions that these data allow us to ask are the following:

- How will the population under 24 years of age -more than 60% of women- experience the change in the government regime?

- How will the literacy rate be affected, especially among young women?

- Will there be data on reproductive health, domestic work and youth pregnancies going forward?

- How will the percentage of the labor force occupied by women change starting now?

GLOBAL CONVERSATION ON AFGHANISTAN EMERGES ONLINE

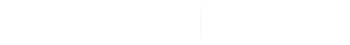

The first analyses of the global conversation on social networks detect a growing concern for the human rights violations of women and children with the Taliban in power, although given the complexity of what is happening, new concerns are emerging. This past August 16th, Signa_Lab performed a download of Twitter’s API (the space designed by the company itself for developers to access data from the platform) through our THOTH (Tweet & Hashtag Observer, Troll Hunter) script with the terms “Afghanistan” or “Taliban,” which yielded 537 thousand tweets.

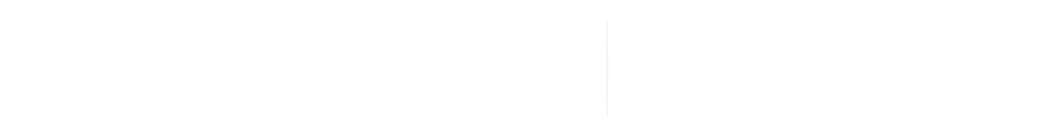

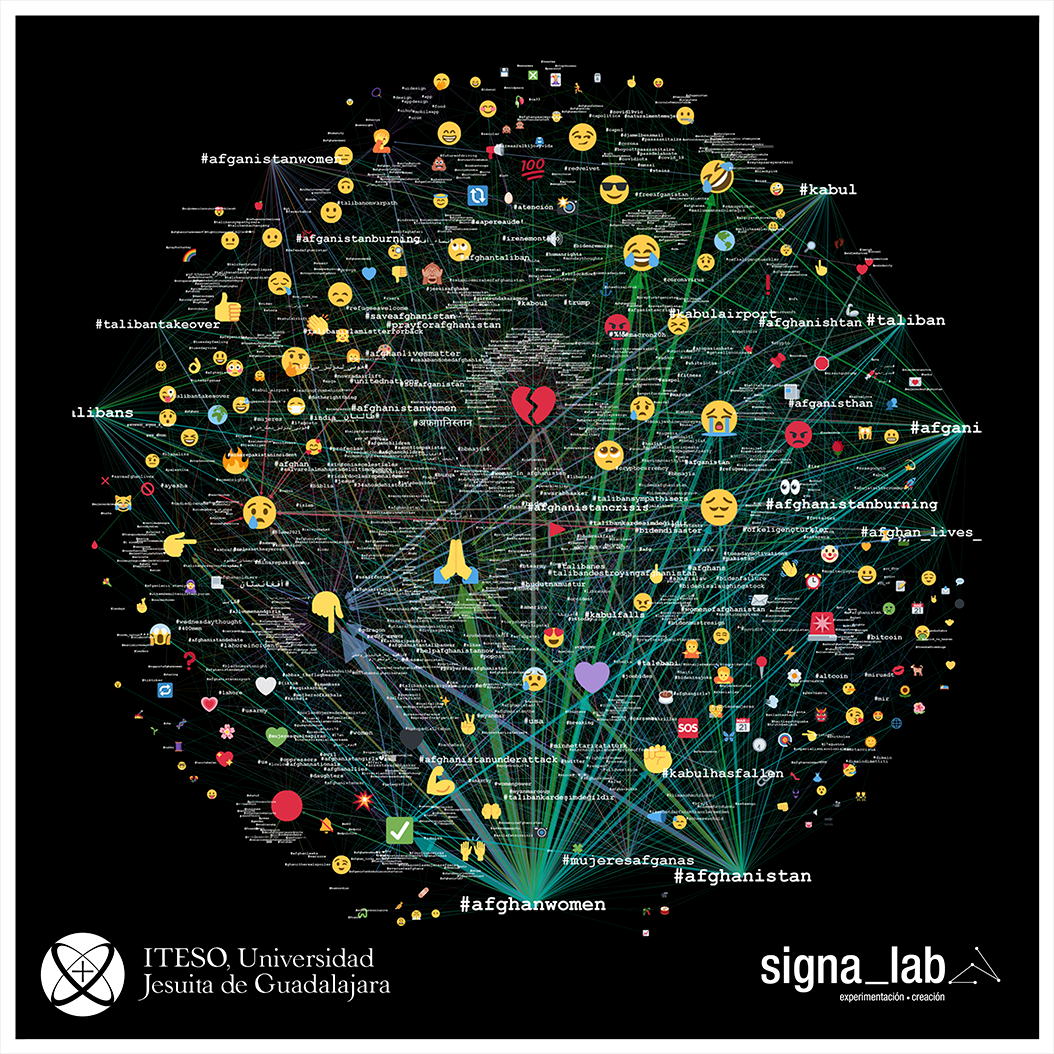

FIG. 4 Graph of relationships between users and hashtags (u2ht) from the download of 128,001 tweets mentioning the terms “AfghanWomen,” “MujeresAfganas” and “AfghanistanWomen” conducted on August 18, 2021. 96,475 nodes, 254,345 edges and 92 communities.

In the conversation, gender-based violence against women began to emerge as one of the most visible issues globally. Searching for “Afghan women” in three key digital spaces— Youtube, Google, Instagram and Twitter—allows us to understand the world’s questions and concerns, contrasted with the experience and perspectives of Humira Saqib.

On Google, up to August 18th, the searches linked to “Afghan women” showed that the links consulted the most up to that moment were looking for the historical and structural context of the situation; the weight of Wikipedia links is evident, as well as the presence of media such as The New York Times, BBC or The Guardian in the top places of the Google search ranking, which indicates that the focus is on the Taliban’s track record of serious human rights violations and the threat that such violations could be committed again in the short term, as has already happened.

These top places of the most consulted sites also include humanitarian aid sites and international activist networks such as womenforafghanwomen.org, hrw.org, unicef.org, feminist.org, girlsnotbrides.org, among others. This points to the fact that people’s concern worldwide is not only to be informed and moderately capable of filtering an overwhelming torrent of links of all kinds, but that people are interested in looking for ways to provide help, especially to women.

Fig. 5. Media, portals and sites by number of links consulted most often on Google with the terms “Afghan women”. Information consultation date: August 18, 2021.

Cloud of URLs referred to most often by Google search engines from the terms “afghan women” as of August 18, 2021. Data obtained with the Search Engine Scraper of Digital Methods Initiative.

The words most often used in the headlines of the media and organizations mentioned in the same download, in addition to derivations of Afghan and Women, show a wide range of words semantically linked to concern, uncertainty and fear, words such as return, fear, voices, organization, girls, dark, rights, among others.

Fig. 6 Words used in the headlines of the 100 links consulted most often on Google with the terms “Afghan women”. Information consultation date: August 18, 2021

Cloud of words used most often in page headlines and articles referenced primarily by the Google search engine from the terms “afghan women” as of August 18, 2021. Data obtained with Digital Methods Initiative‘s Engine Scraper.

This concern is amply justified. Saqib notes the following:

“A few days ago in one province they killed a woman for wearing a colorful dress and in the capital they are already starting to hunt women working in government, media and schools. Fear was felt and grew greater as the Taliban approached the city. There were no cars, stores were empty, windows were closed, children did not go out to play and the only people who left their homes did so to go to the airport or to try to leave the country by land.”

The production and reproduction of videos on YouTube with the words “Afghan women” in the title skyrocketed in the first few days of the week of August 15-22. Those first days concentrated the highest number of reproductions with 460 videos being played and shared constantly. Those with the greatest reach accounted for around 1.5 million views in their first days of publication. Of the international media to which the videos belong, CNN, BBC, NBC News, and Al Jazeera English stand out. The following visualization allows you to navigate through the videos and the channels to which they belong. In the second tab you can compare the videos by volume of reactions (number of views, number of likes, number of dislikes and number of comments).

Views of 460 videos posted on Youtube from August 15 to August 22, 2021 listed as the most relevant according to the platform’s search algorithm, based on the terms “afghan women”. Data obtained with Youtube Data Tools de Digital Methods Initiative.

Below are two word clouds generated from the downloads on August 16 and 18, with the terms “afghanwomen,” “mujeresafganas” and “afghanistanwomen.” Tweets were filtered by language, English and Spanish.

Signa_Lab conducted a couple of Twitter downloads with the same keywords or terms of reference (Afghan women). The first, on August 16, yielded 60,691 tweets; the second, conducted on August 18, yielded 128,001 tweets.

This cloud shows the 785 most frequent words used in English-language tweets:

Fig 8. Cloud of the 785 most recurring words in the content of English-language tweets downloaded on August 16 and 18, 2021 that mentioned the terms “AfghanWomen”, “AfghanistanWomen” and “MujeresAfganas”.

The following cloud shows the 836 most frequent words used in tweets in Spanish:

Fig. 9. Cloud of the 836 most recurrent words in the content of Spanish-language tweets downloaded on August 16 and 18, 2021 that mentioned the terms “AfghanWomen”, “AfghanistanWomen” and “MujeresAfganas”.

Interestingly, despite the huge linguistic differences between Spanish and English, there is a strong overlap in the narrative constructed and shared on social networks about Afghanistan, indicating that the language of human rights and the concern about the consequences of the Taliban regime for the respect of human rights is universal.

THE EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONS

As we have pointed out in previous reports, we consider that emojis have become an epochal language that imprints different affective tonalities on digital conversations; emojis construct a politics of affects or emotions. Their use, interspersed with hashtags, images, gifs and words, constitutes a system that allows nuances to be introduced in the study of large volumes of data.

For this analysis, the hashtag-emoji relationship was used through the hashtag #afghanwomen. It is of interest to analyze the symbols as a way users strengthen their affective involvement.

In the visualization shown below, the emoji with the greatest relevance is the broken heart; it is associated with hashtags such as #americantroops, #afghanistanwomenandgirls, #donate, #rescuetherescuers, #kabullady, #herstory, #talibaan, #freedom, #wokemilitary, #wherisbiden, #whereskamala, #egoisme, #indiacrying, #isisis, #humanrightsviolations, #clarissaward. The relevance is given by the size of the emoji, which is possible to analyze through a script developed in the lab that reviews all the tweets present in the download and extracts those containing emojis and hashtags together in the text of the tweet, and then counts how many times they appear together in the whole download. This is exported in the logic of nodes and edges so that it can be visualized in Gephi.

The #clarissaward tag refers to the moment in which one of the Taliban present in the American journalist’s coverage asks her to cover her face as one of the many rules that women have to follow in order to remain in public space. But they also limit her space and demand that she step aside as a sign that the space belongs to them. This situation frames the context of extreme violence to which women allow themselves to be subjected in order to maintain their physical integrity.

In this network of emojis, we can appreciate the level of scale from higher to lower link between icons that refer to laughter or mockery, so we decided to look carefully at the hashtags to understand how these images took shape in social networks around an emotion that, placed in the collective feeling, contrasts with the expressions of concern, pain, and sadness over a humanitarian crisis that cries out for human rights.

In our exploration, we found that some profiles or accounts push different agendas that generate distortion in the conversation, “piggy-backing” on trends that millions of users are reading or reviewing, so that the mockery, which reaches a certain relevance, is not necessarily linked to the issue of Afghan women.

Fig. 10 Graph of relationships between hashtags and emojis (ht2emo) from the download of 128,001 tweets mentioning the terms “AfghanWomen”, “AfghanistanWomen” and “MujeresAfganas” made on August 18, 2021. 1226 nodes (222 emojis and 1004 hashtags) and 3969 edges.

Finally, in a nod to the importance of pets, even though their relevance did not reach enough mentions, the symbol of dogs and cats has been present in the conversation as a way to express an additional concern for the thousands of Afghans who have had to leave their pets behind in the attempt to escape from the new government. The graph can be navigated with the magnifying glass placed over the image.

IMPLIED GAZES: THE IMAGE AS THE PRODUCTION OF MEANING

Instagram has been another space for the discussion and dissemination of the conflict in Afghanistan, but as a primarily audiovisual platform, it is also a key platform for the collective construction of an aesthetic, i.e., a way of looking at and representing some of the edges of the humanitarian crisis in that country.

The hashtags have been diverse and varied in scope. More than 3.2 million images use the hashtag #Afghanistan (posts mostly in English) and about 458 thousand use #Afganistán (in Spanish). #AfghanWomen, one of the tags we analyzed, has more than 51 thousand posts as of August 22. In the following word cloud are the 500 tags used most often. We performed a download using a scraper that searched for images with this last hashtag.

Fig. 11. Cloud of the top 500 tags used most often in Instagram posts mentioning #AfghanWomen as of August 22.

The hashtag analysis indicates that among the hashtags used most frequently, #AfghanGirl appeared in third place, in reference to the younger women who are being affected by the conflict; in seventh place was #HumanRights, due to the concern about violations of women’s rights in Afghan territory. The tags also seek to draw attention to the need to support the civilian population (#SaveAfghanistan, #PrayForAfghanistan, #FreeAfghanistan, #HelpAfghanistan, #StopTaliban).

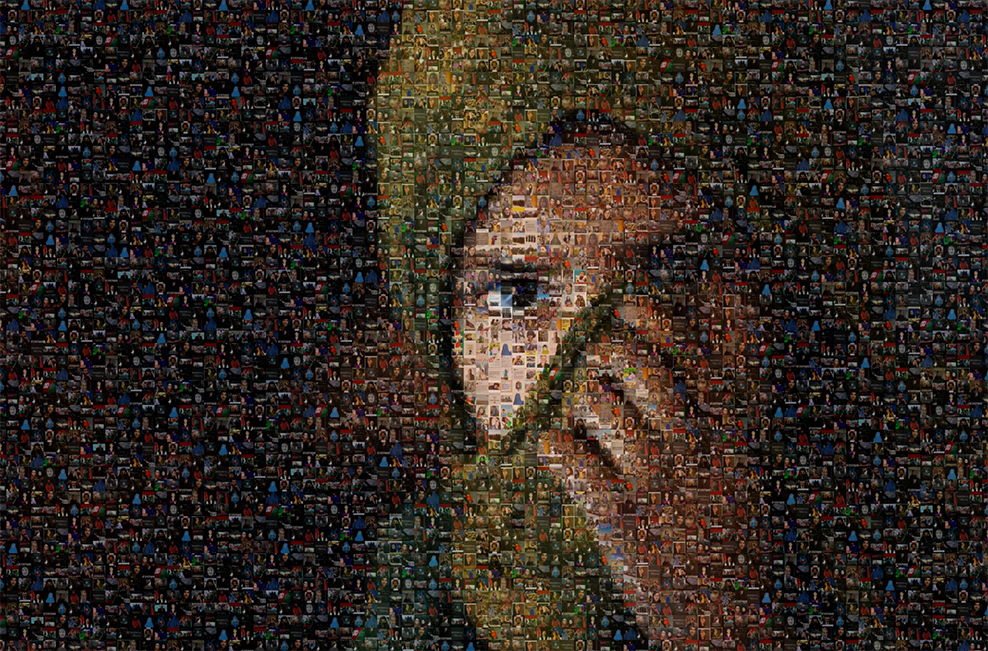

The images are mostly portraits of women, followed by selfies and photographs that possibly come from news services.

For the visualization of this download, we constructed “a mural” in which all the individual photographs form the image of a woman wearing a hijab, a veil that some Muslim women wear to cover their hair and sometimes their neck. The mural also features photographs of women with uncovered faces that are published as a way to show solidarity with Afghan women.

The posts with more than 500 likes in the download mentioned above were chosen, resulting in 222 photographs. In addition to those already mentioned, there are also photographs of the Afghan flag with its three colors (black, red, green), as well as texts and slogans in support of the Afghan population.

Fig. 12. Mosaic with the 222 images in Instagram posts mentioning #AfghanWomen that had more than 500 likes by August 22, 2021.

Note: we suggest zooming in to appreciate the photographs that make up the mural.

THE MEDIA AS A STRATEGY AND AS AN ENEMY

Another central issue in these first days of global concern about the situation in Afghanistan has been freedom of the press. International media started issuing alerts as soon as the first images from Kabul airport were made public, showing hundreds of people invading the runways, trying to board any plane that would take them out of the country. The images of people clinging to the fuselage of planes and the report of human remains found in the landing gear of a U.S. military plane conveyed the terror that thousands of Afghans feel at the prospect of living under the group accused in 2001 of harboring Al Qaeda while planning the attacks against the Twin Towers in New York.

Abdullah Ahmadi, director of the Afghanistan Democracy and Development Organisation (ADDO), who also had to flee the country in recent days, comments in an interview with Rodrigo Sosa:

“The Taliban have already had some press conferences and interviews and they said that they are going to respect journalists and civil society. They pledge that they will let them do their job but from the experience we have had and from some reports, we know that it is not going to be like that. We have some reports of how they have already fired some colleagues from television and how they are looking for others. There are many journalists in really tragic situations and that is why they are trying to flee the country and are looking for organizations in Europe or the United States. It is not just about firing people; the Taliban want to kill activists and journalists who can tarnish their image with the international community. They have not changed, although they want to make the media believe that they have. They want to change their image but we know that what will happen is that they will impose Sharia.”

This view is shared by Saqib: “With the Taliban regime, freedom of expression in Afghanistan is over,” she says. The media outlet where she herself writes is under siege:

“Many of our contributors are already out of the country; those who stayed have had to leave their homes and go into hiding because the Taliban are looking for them. They go from street to street emphasizing that Taliban law must be obeyed and that no one should hide anyone.”

Ahmadi emphasizes the anti-media moves that the Taliban have already carried out and of which he already has confirmed knowledge:

“The Taliban already have control of national television. They removed from the programming any newscast or program that has women in it. Only music or religious programs are left on television and radio.”

However, the face of this generation of the Taliban elite has not been the same as it was at the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, when intransigence was their only form of relationship with other governments and their main discourse before public opinion.

So far, the strategy has been to show openness to dialogue with other countries, the affirmation that women’s rights and freedom of the press will be respected, always with a caveat— a promise to respect “within the framework of Islam.” They have even appeared in interviews in international media seeking legitimacy through the presentation of a moderate image. For some analysts, this behavior may be part of a strategy that effectively seeks to establish a regime that is less violent and more willing to dialogue with governments of different countries (especially the United States, Iran, Pakistan, China and Russia), which would allow it to offer certain acceptable margins of stability within the international community. For people like Humir Saqib, however, this is nothing more than a façade that papers over serious human rights violations:

“In theory, the national radio and television media are still functioning normally, as are the newspapers, but I have information that many journalist colleagues are no longer allowed to enter their offices, others have been fired, and others have received threats. The Taliban already control the national radio and television broadcasts and fill them with propaganda or extremist journalists. And they control not only violently but also from the internet.”

International coverage of the media in Afghanistan up to August 22 shows that on Google, the headlines are about three main concerns: the killing of journalists, threats, and the uncertainty of future freedom under the return of the Taliban regime. The following visualization shows the words used in the headlines containing the words “Afghan media” that were most often consulted on Google up to the date mentioned:

Fig. 13. Words used in the headlines of the 100 most consulted links on Google with the terms “Afghan media”. Information consultation date: August 22, 2021

Against this background, it can be argued that the media have a double role for the Taliban regime: on the one hand, they are a space through which an acceptable image for the international community must be constructed, by softening the discourse against women’s freedom and the media, always from the standpoint of their particular reading of the Koran; and on the other hand, it is a set of internal and external actors who, insofar as they are not under the control of the regime, pose a threat to it and to the unrestricted imposition of its law in Afghanistan.

SOCIAL NETWORKS, REAL-TIME CATASTROPHE AND GETTING THE INFORMATION OUT

While all this is happening, the volume of information produced and the speed at which it circulates show us once again some of the implications of the acceleration and viralization of reality in the contemporary era, including:

- The difficulty in filtering information and finding valid and serious sources.

- The difficulty in keeping abreast of the most relevant information about an event with real-time updates.

- The role of algorithms and the rules of social networks to interrupt or allow the spread of content on a chain of events where the lives of people and the political stability of a country or region are at stake.

Regarding the first two, it is important to highlight that the massive production and circulation of information on digital media about the seizure of Kabul on August 15th, both graphic and written, took place practically in real time. This vast flow of data and information that flooded the networks and shocked millions of people around the world aroused instant global interest in learning more about the reality faced by Afghan society in this new scenario; however, the speed at which information flows makes it hard to be sure whether the news being consumed has the necessary filters to separate sensationalism from legitimate information that provides context, or immediacy from confirmation of the information. Speed, in most cases similar to this one, favors the circulation of content that generates emotional reactions rather than analysis or questions.

During the takeover of the Afghan capital, images of the airport and an image of a military plane crowded with more than 600 passengers fleeing the country were repeatedly circulated. Several of the most shared tweets showed people falling from planes that had just taken off in Kabul and chaos at the airport. At first, the information about the origin and background of the plane full of fleeing people was not clear: there were rumors that it was an Indian plane evacuating Afghan citizens, but this was confused with information stating that at the time the Indian border with Afghanistan was blocked and with the confirmation of the departure of the Indian ambassador to Afghanistan. It was not until the following day that it was confirmed that the plane in the picture was a U.S. Air Force plane, bound for Qatar, that had evacuated as many people as it could at the last minute, 640, during the chaotic scenes at Kabul airport on August 15th.

The interactive visualization below shows a word cloud with the conversation of 99,001 tweets that used the terms “Kabul plane.” Among the words mentioned most often are: Kabul, plane, airport, people, military, shows, falling, image, video, trying, hanging, clinging, scenes. From the chaotic context in which the conversation emerged, it is possible to read the desperation, the absorption and the confusion in the face of a massive stream of information that was not confirmed until hours later. The speed of social networks contributes to the worldwide communication of a historical event in real time, but it also generates multiple lines of attention that may well make people take notice due to the tragic nature of the situations in question; however, they probably contribute more to producing a superficial, sensationalist reading of the event that does little to help people determine which of the versions circulating is true, and even less to give them insight into the broad context of the event being reported.

Fig. 14. Words used at least 100 times in tweets with “Kabul plane”.

The turmoil of the subject and the flooding of digital spaces with content created and reproduced without the same effort in verifying the sources of information, complicated the understanding of what was happening, and also represented an obstacle for other types of testimonies to be heard in those same moments. The images of the airport overrun with people and the crammed airplanes left an unmistakable impression of the desperation of thousands of people trying to flee to a foreign country, but they also effectively hijacked users’ attention and crowded out any other focus of conversation from the networks. While the visibilization of an event is in itself an important resource for understanding the topic, it is also necessary to think about possible frames of the conversation that are not addressed when one line of the conversation (desperation) is the primary center of attention.

Regarding this last point, applying filters to the navigation of the conversation centered on the planes also shows some tweets that rather futilely tried to put in perspective what the responsibility of the US and allied governments was, if after twenty years of occupation in Afghanistan this was how they were leaving the country’s capital.

With respect to the role of network rules and algorithms in the spread of information, Facebook has said that in Afghanistan it has decided to restrict the circulation of posts related to the conflict and has prevented other profiles from accessing the contact list of people sharing information about the crisis, with the intention of “protecting people” from possible attacks.

In the content distribution guidelines of this social network there is an explicit rule to reduce the spread of publications that incite violence or crimes. During the protests in Colombia in May and June 2021, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter were accused of restricting the circulation of publications that denounced police violence against protesters. The Facebook team responded that it could have been due to its moderation algorithms, which seek to maintain a safe environment on its platforms, so they inhibit posts that they interpret as possible incitements to violence. Facebook assured it was working on knowing how to discern cases of public interest and label them as “sensitive material.” For its part, Facebook’s Content Advisory Board (Oversight Board) identified in one of these cases that the reason for blocking a video covering the protests in Colombia was the use of language in the slogans, which when translated into English was interpreted as expressions that incited hatred and, therefore, went against its standards. However, these measures may not necessarily work to achieve the objective of guaranteeing a safe environment, because blocking the spread of publications that show crimes being committed, especially by authorities, may make the difference as to whether these crimes continue to be committed or not, and whether local and international pressure can help to stop or reduce the risks for the civilian population.

While this is happening, journalists like Saqib are beleaguered by the regime’s aggression, which is not only physical, but also psychological and virtual:

“We are dedicated to reporting issues related to the situation of women in Afghanistan and their human rights. Well, our website was hacked yesterday. We are a small media outlet; we don’t have much of an international presence but now we can’t access anything on our site. We still can’t be sure if it was a coordinated attack but we believe it was…”

Abdullah Ahmadi’s testimony is similar. He tells us: “… there is a lot of digital restriction and on some social networks like Facebook they also track opponents by searching for certain words.” Because of this, they have decided to use only certain networks: “WhatsApp, Signal and email. It is very dangerous to use the cellphone network because many are tapped. We also use Facebook, but less and less.”

The complexity of the events in Afghanistan is evident: after multiple conflicts and 20 years of U.S. occupation, plus another 20 years of conflict pervaded by the aftermath of the Cold War, the situation is extremely worrying, not only for the Afghan population but for the whole world. There is one huge difference between the Taliban regime installed in 1996 after the civil war in Afghanistan – a regime that was overthrown in 2001 by an invasion led by the United States – and the current control and takeover of the capital Kabul and with it, the government, and that difference is the existence of socio-digital networks that operate in three dimensions that are key to reducing the risk of an extreme radicalization of Sharia: ubiquity, speed and immediacy. The whole world is now aware of what is happening; information, images and documentation circulate, as we have already pointed out, in real time. This will have major implications, and it cannot be ruled out that precisely because of these networks’ ability to make things go viral—things like protests, or resistance, or documentation of human rights violations—the response of the Taliban regime will be to simply shut down the Internet. This raises many questions.

In the midst of the chaos of the flight of thousands of people captured in images at Kabul airport, the acceleration in the production and circulation of videos and images on social-digital networks continues to show the difficulties of filtering so much information in real time and the risks that the conversation will end up feeding into the lack of context and confusion about what is happening. While millions of people shared the image of a plane overrun with people, without knowing exactly which government it belonged to or where it was going (as a correlate to the chaos that people in that place were actually going through), some users, without much impact on the trends revolving around Afghanistan, wondered about the implications of the return of a local government headed by the Taliban after 20 years of foreign occupation, while pointing out the responsibility of the occupying powers. The balances in the digital conversation determine the impact of one or the other way of framing the event.

Finally, the biases of algorithms and of the policies that regulate publication, which condition the spread of content on social networks at times and in spaces where it can be assumed that serious human rights violations will occur, continue to be a challenge for the necessary influence of voices from academia, journalism, activist groups and national governments themselves in these decisions. Cases such as Afghanistan and the protests in Colombia in May 2021 make it urgent to raise the debate of this issue to the global level.